A man from London is now considered as the second person ever cured of HIV.

The man’s case was first announced a year ago; and he has now been HIV-free for 30 months, not needing antiretoviral medications (ARVs), according to a report published in The Lancet HIV.

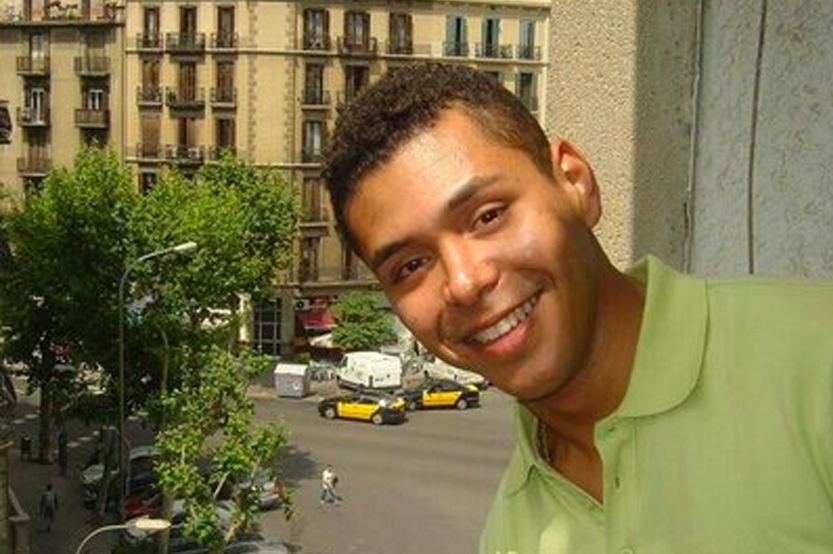

The man was previously known only as the “London patient”; but his identity was revealed just as this development came into view.

Adam Castillejo is a 40-year-old who grew up in Venezuela. He was first diagnosed with HIV in 2003 after moving to London a year earlier, and developed advanced Hodgkin lymphoma in 2012. In 2016, to fight the rare cancer, he received bone marrow stem cells from a donor with a rare genetic mutation that resists HIV infection.

Last year, he experienced “long-term remission” from the virus after undergoing a special bone-marrow transplant. At that time, he was already HIV-free for 18 months. Now, 12 months later, his doctors are “more sure” that his case does indeed represent a cure.

In a statement, Ravindra Kumar Gupta, a professor of clinical microbiology the University of Cambridge and the lead author of the report published in The Lancet HIV, said: “We propose that these results represent the second ever case of a patient to be cured of HIV.”

The first patient to be cured of HIV is Timothy Brown, who was earlier known as the “Berlin patient”. He also received a similar bone-marrow transplant in 2007 and has been HIV-free for more than a decade.

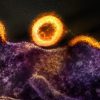

In the two cases, stem cells used for their transplants came from a donor who had a relatively rare genetic mutation that confers resistance to HIV.

The researchers, nonetheless, stressed that such a bone-marrow transplant would not work as a standard therapy for all patients with HIV because: 1. such transplants are risky, and 2. both Castillejo and Brown needed the transplants to treat cancer rather than HIV.

In the new report, doctors found no active viral infection in Castillejo’s body. But they found “remnants” of HIV’s DNA in some cells (traces of DNA that can be considered as “fossils” because they are unlikely to allow the virus to replicate). Such remnants were also found in Brown’s case.

The second cure is now taken to mean that the first one (in the Berlin patient) wasn’t an anomaly or a fluke.