“We cannot deny the fact that there are people who will really discriminate us (people living with HIV),” said Robin Charles O. Ramos, who is based in Digos City in Davao del Sur in Mindanao, southern Philippines. “(But) think twice… before you discriminate because (everyone can be infected with) HIV.”

BI AWAKENING

Charles, 33, used to be only attracted to girls. But when he was nine years old, “I (was also) attracted to boys. I realized that I am attracted to both sexes.”

Charles’ family teased him for this. But he added that it’s not like they can prevent him from being bisexual; this “runs in the family,” he said, with other family members also LGBTQIA.

“It was somewhat difficult for me to come out,” he said. This is because he lives in a “relatively small community (where people know me).”

Digos, a 2nd class city and the capital of the province of Davao del Sur, has a population of only 169,393 people (in 2015).

But Charles eventually told others, realizing the relevance of being true/honest to oneself. “I know it (may not be easy) but… the community will (eventually) understand who and what we are.”

FINDING OUT ABOUT HIS HIV STATUS

On November 30, 2017, Charles found out he has HIV.

Prior to the diagnosis, he recalled having bad health – e.g. his cough wouldn’t go away, he had lymph nodes in his throat, he easily got tired/stressed out, and he had recurring fever. He self-medicated, “taking paracetamol” and antibiotics.

“I lost a lot of weight,” Charles recalled, “from 56 kilograms to 48 kilograms.”

At that point, his mother told him: “It’s time to rush to the hospital.”

The attending physician had Charles undergo more tests… including HIV antibody test.

The person who gave him the news about his HIV status was “actually a friend of mine.” In fact, he pre-empted the counselor from telling him the result; “I told her myself, ‘It’s positive, right?’.”

EVERYONE CAN BE INFECTED

Even before then, Charles actually worked in HIV advocacy.

So the person who gave him the news about his HIV status was “actually a friend of mine.” In fact, he pre-empted the counselor from telling him the result; “I told her myself, ‘It’s positive, right?’.”

That was also “mind conditioning” for him, he said. “I conditioned my mind that I’m positive already… it’s a way of acceptance of the matter.”

Right there and then, Charles opted to tell family members. And they had one question for him: Why him, considering he’s in HIV advocacy, and should know better?

“Anyone can be infected,” Charles said to them.

“Think twice… before you discriminate because (everyone be infected with) HIV.”

BEING OPEN ABOUT LIVING WITH HIV

If there’s one thing Charles said that’s good about being out, it’s being able to get external help as needed.

“I lose nothing by coming out,” he said. And for him, “PLHIVs need to come out… as a strategy for us to eradicate stigma and discrimination.”

At this stage in his life, “I don’t care if they talk about me. This is already here. Just accept it.”

Charles is also a teacher, and he opted to tell his supervisors and peers about his medical condition. This honesty paid off since “they support me.” His workmates always remind him to “not be stressed” and “have time to rest”.

HIV-RELATED ISSUES IN DAVAO DEL SUR

HIV screening and/or testing is, at least, accessible to the people of Digos City, said Charles. The social hygiene clinic (SHC) of the local government unit (LGU), for one, offers this; and “every time we conduct (gatherings) about HIV, there is HIV testing (given).”

It is the access to life-saving medicines (the antiretroviral treatment, or ARV) that is problematic.

“Here in Digos City, ARV is not yet available,” Charles said.

And so PLHIVs from there have to go to the Southern Philippines Medical Center (SPMC) in Davao City, which is 62.5 kilometers away (or approximately an hour of commute).

If there’s one thing Charles said that’s good about being out, it’s being able to get external help as needed.

Many of the PLHIVs from Digos City go to SPMC together, renting a van to take them to and from Davao City for their regular tests and ARV supplies.

A related issue: PLHIVs have to go every month because they are only given a month’s supply because of procurement issues. The usual practice is to give PLHIVs supply for three months. And – even if the Department of Health denies that there are issues concerning ARV supplies – at least the Digos City experience highlights the continuing difficulty with accessing life-saving medicines.

The dream for PLHIVs like Charles is for a refilling station to be established in Digos City to serve not only those living there, but also the nearby localities of Kidapawan City, Davao Occidental, et cetera.

EMPOWERING THE HIV COMMUNITY

Charles recognizes that many try to help PLHIVs, but he also thinks that empowering PLHIVs to help each other is essential.

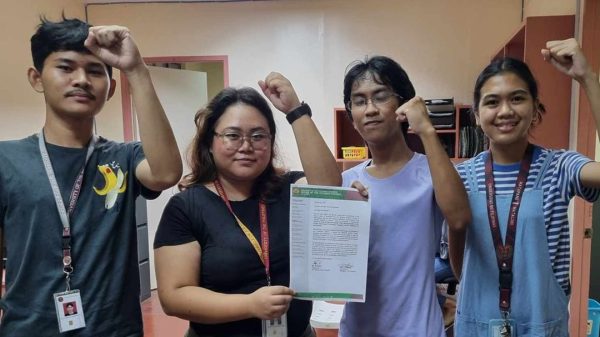

“We have formally created a group: Bagani Southern Davao,” he said. The name was derived from the word “Bagani”, the peacekeeping force of the Manobo tribes and other indigenous groups in Mindanao. Akin to the word, “we’re warriors; we’re fighting against this illness.”

There are currently 20 active members; though, of course, not all PLHIVs in the area are members.

The dream for PLHIVs like Charles is for a refilling station to be established in Digos City to serve not only those living there, but also the nearby localities of Kidapawan City, Davao Occidental, et cetera.

To other PLHIVs in the area, Charles said he recognizes that it may take time before they can decide if they’d come out. “I respect (this) decision… But coming out as PLHIV is a way of educating people that they shouldn’t fear us, and that (having HIV) isn’t the end of our lives or the end of anything.”

As PLHIVs, he said, “we have more to offer, more to do” particularly in educating people.

And to non-PLHIVs or those who do not know their HIV status: “Know your status. Get tested. And stop discriminating people. It’s not like we wanted this to happen to us. But this is already here. We just need your support, and the respect that we want because we’re still human beings.”

“I lose nothing by coming out,” he said. And for him, “PLHIVs need to come out… as a strategy for us to eradicate stigma and discrimination.”