It was the 20th of May 2000 when I walked into the doctors’ rooms to get the test results from my HIV test. Sitting across the desk of my doctor, I received the news that I only had three to six months to live because I was HIV positive and because the infection was far advanced.

But there was a glimmer of light: IF – and it was a very big IF – it was possible to access antiretrovirals (ARVs), so that my prognosis would be very different. In 2000, antiretroviral therapy (ART) was only available in South Africa to the privileged few who could import it privately.

“Low levels of caring response can only see an increase in terms of further HIV transmissions in a growing pandemic where the already challenged public health system is stretched beyond ability to respond. The time to change is now before it is too late,” says Rev. Fr. JP Heath.

In just two months, then President Thabo Mbeki would make his statement at the Durban International AIDS Conference that HIV did not cause AIDS, and the denial in South Africa would be in full swing. By contrast, European countries were not only making ARVs available for people living with HIV (PLHIVs) but were using African countries as guinea pigs in terms on how to control side effects.

It was into one of these drug trials that I was eventually admitted – i.e. a drug trial run from Amsterdam and executed in Johannesburg. A drug trial which looked at the introduction of steroids during the initial phase of treatment to reduce side effects related to antiretroviral therapy. The only way of monitoring side effects effectively was through blood tests, and so my blood was drawn in Soweto but tested in Amsterdam. The net result was an artificially created time lapse between test and result. A time lapse that nearly cost me my life.

It was only four years later, and with significant pressure from the Treatment Action Campaign, that ARVs became available for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission, and still much later for adults living with HIV in South Africa. While ART has been introduced, it was very clearly under duress, and we had to suffer under a constant litany from the then minister of health. Then, the only effective way of treating HIV was eating beetroot and drinking lemon juice and olive oil.

Accessing ARVs through the public health care system in South Africa involved a nail-biting wait on a waiting list. Your immune system had to be sufficiently depleted and only when the severely eroded immune system had been achieved did you enter into the waiting period for the available waiting slots. And so when you are eventually accepted into treatment, you knew that there was another one whose treatment failed and died to make the slot available for you.

Accessing treatment meant the once-a-month full-day sitting in endless queues to receive a script for one more month of medication. Somehow you were supposed to maintain the illusion that you could hide your HIV status if you wanted to. Choices of medications were extremely limited. Constantly one would hear of new drugs which was successfully being used in Europe and America which had not been licensed by the South African Medical Association. Whole new families of ARVs had been developed and were changing people’s lives but they were rainbows in the sky, not touching earth in Africa.

In January 2012, I moved to a new job in Sweden. Among the first things I did was to go to a hospital to be able to avail myself of the medical care offered by the Swedish state. Suddenly a viral load test was no longer an optional extra but an integral part of monitoring disease control or progression. Similarly, ARVs were prescribed according to their efficacy and in relation to your own body’s ability to tolerate side effects. And then they came the resistance tests. Who knew such a thing even existed?! The virus in my body was being put through a test to determine with the South African conditions, and if I have developed a resistance.

What was of critical importance in the Swedish system was that in my therapy, I achieved total viral suppression. Not only for my own health’s sake, but because of the clear understanding that effective treatment is also effective prevention. In Sweden, I was not merely another number who had to be fitted into the government protocol of available medications. But I was a patient with individual needs, unique side effects, and have compassionate doctors seeking to respond to my body’s individual needs in terms of ART.

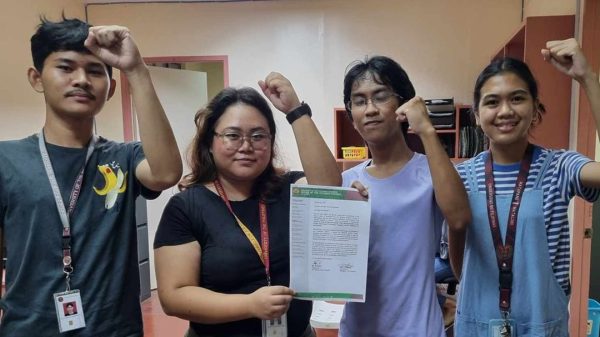

On visiting the Philippines, I was privileged to meet a number of people living with HIV. Their stories and testimonies of the level of healthcare available in the Philippines both shocked and horrified me. While World Health Organization (WHO) protocols are followed, the choice of available drugs, the long waiting periods, and the frequent stock-outs were all too reminiscent of my experience in South Africa. But while South Africa, which has a population of 55 million people, provides ART to two million people, the relatively small number of people related to 100 million people in the Philippines makes the level of care provided to PLHIVs indefensible.

Low levels of caring response can only see an increase in terms of further HIV transmissions in a growing pandemic where the already challenged public health system is stretched beyond ability to respond. The time to change is now before it is too late.